PITCHER PLANTS

There are several other pitcher plants beside the side-saddle plant, and they all behave in the same peculiar way, setting traps to catch the unsuspecting little insects which come to visit them for the sake of the honey so temptingly spread out to deceive them. But these insect traps are not all exactly alike. They are sometimes straight, sometimes bent and twisted. Some pitchers are like funnels, trumpets or vases, others are like jugs or curiously-shaped mugs with handles all complete. Some protect the entrance to the trap with a lid or hood to prevent the rain from falling in, others allow the rain to enter, so that they are always half-full of water. In this the insects they catch are drowned and converted into a sort of insect soup.

One of these insect-catching plants, found chiefly in California, rejoices in the long name of "Darlingtonia." Like the side-saddle plant, its stemless leaves rise in clumps from boggy ground, and are joined to form a hollow tube. But instead of being straight and trumpet-shaped, each leaf is twisted, and the top curves over like a large hood, or helmet, hiding the entrance to the pitcher. A large bright purple streamer hangs out in front of the entrance to catch the eye of flying insects and show them the way in, and the helmet itself is gaily marked with splashes of red or pearl, and it is dotted all over with transparent spots, like so many little windows which glisten in the sunshine.

Like the side-saddle plant the Darlingtonia has a narrow pathway leading from the ground to the mouth of the pitcher, for the convenience of ants and other crawling creatures eager to find out what there is to be had at the top of this strange looking plant. But dearly these inquisitive insects pay for their curiosity. Few which climb that winding path ever return again. The rim of the pitcher is smooth and curves gently inwards, so when the little travellers reach the end of their journey and peer over to see what there is inside, they loose their footing, tumble over, and go slipping and sliding all the way down to the bottom, where a barrier of bristling hairs prevents them from ever climbing up again.

The same fate overtakes the flying insects when, enticed by the bright fluttering streamer, which in the spring and early summer is sprinkled with honey drops, they foolishly venture over the curving edge of the pitcher. Alarmed at what they see below, the startled insects try to fly out again; but they fly up inside the helmet and beat themselves against the transparent glassy spots in a vain attempt to reach the outer air - just as flies beat them selves against a window pane. The foolish insects never think of looking for the exit at the bottom of the helmet, but keep banging themselves wildly against the top of it, until at last, tired out with their struggles, they fall back into the pitcher again - very few indeed manage to find the right way out.

Although they are commonly called "pitcher plants," the side-saddle plants and the Darlingtonia of North America are not really so much like pitchers as the insect ogres that live in the swamps and by the jungle pools, in the tropical parts of the old world.

There are about forty different kinds of these true pitcher plants. Some are quite small and pretty little little things, able only to catch such small fry as flies and ants for their dinner, others are so big that they are said occasionally to trap the bright little birds that flit about in the great tropical forests; while the largest pitcher of all is so big that if a pigeon should chance to fly into it the bird would be completely hidden.

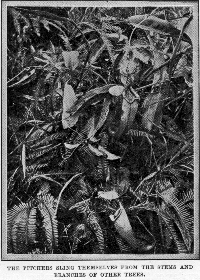

In the true pitcher plants the whole of the leaf is not rolled round to form the insect-trap, like the leaves of the side-saddle plant, but is divided into three distinct parts. The lower part is broad and flat and green, just like an ordinary leaf; then comes a long, slender tendril which coils like a snake round the stem or branches of any other plant it can manage to clutch, and at the end of this hangs the curious pitcher. Very often the pitchers are slung over the water in this way, upon the branches of trees growing by the side of a jungle pool.

Quite young pitchers are tightly closed with a lid, and are often covered with a downy coat, which may be a rusty red or a glittering golden color; while some rare kinds are as white as snow, or look as if the were powdered all over with flour. After a while the lids open and the pitchers loose their hairy coat. They are then a yellowish green color with veins and splashes of purple; while near the opening many are tinted blue, rose-pink, dark red, blue or violet. The lid that stands above the open mouth of the pitcher is always most brightly colored, and the rim round the mouth may be brown, yellow, or orange-red. From a distance these gaily-colored pitchers look just like beautiful flowers, so it is not at all surprising that winged insects flock from afar to visit them.

Underneath the lid and all round the fluted rim of each pitcher is an abundant supply of honey, which flows from a number of little honey-pockets in the leaf. This, of course, delights the insect visitors, who lose no time in sucking up the sugary drops. As long as they stay in the lid the insects are safe enough, but sooner or later they are almost sure to wander on to the rim round the open mouth, where the honey is particularly tempting and plentiful.

The rim of the pitcher curves gently inward, but the insects are so busy and happy lapping up the honey that they pay no heed to this, until suddenly they find themselves slipping over the edge. They try to save themselves and regain their footing but this is not easy, for the inside of the pitcher is coated with slippery wax, and before they realize what has happened the frightened little creatures are toboganning swiftly down to the dark pool of water at the bottom of the trap. There they are quickly drowned, for though some may crawl out of the pool and try to climb up to the top again, they cannot mount that steep and polished pathway, and they always fall back into the pool again. Some of the larger pitchers even have a row of sharp teeth, just under the rim, which point down-ward, to make to make sure that none of the prisoners can by any chance escape.

The liquid with which the pitchers are almost always almost half-filled is not rain water but an acid fluid which oozes from special gland-cells in the wall of the pitchers; and this fluid quickly dissolves and digests the soft parts of the victims. The funny little lemurs that live in the trees in the forests sometimes go fishing in the pitchers with their long-clawed fingers, and help them selves to the contents; but to prevent the little robbers form stealing their food some of the big pitchers have a pair of strong, long prickles, jutting out from just below the lid, which prick the little robbers and punish them severely if they if they try to take anything out of the living insect traps.

The lemur, as perhaps you know, is an odd little animal something like a monkey. Its home is in the forests in the hot countries across the seas, but you may see one any day if you go to the zoo.