FLY-CATCHERS

Besides those wonderful insect-catching plants that move almost like animals to seize their prey, and those which catch unwary insects in cunningly contrived snares and pit-falls, there are yet others which, although they are not able to move, like the sundew and Venus's fly-trap, and have no insect traps like the pitcher plants and the bladderwort, manage quite well, in spite of this, to secure a sufficient supply of fresh animal food to make up for the lack of nitrogen in the soil in which they are rooted.

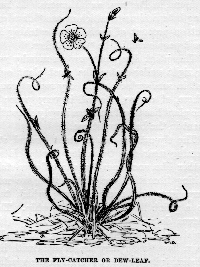

One of the most remarkable of these plants is found in Portugal and Morocco. It has a, long botanical name which means " dew-leaf," but on account of its habit of catching flies most people call it the "fly-catcher."

This plant does not grow on marshy spots or right under water like most plant ogres, but in sandy places or on dry rocky ground, where, of course, the soil is very poor; so the plant has to get an extra supply of nourishment in the best way it can.

The fly-catcher has a stout central stem bearing near the tip a few pretty flowers, rather like anemones, on short flower-stalks. Rising from the base of the stem are many very long and narrow leaves, which taper to a point like the lash of a whip. These leaves do not stand up quite straight, but twist and curve in a snakey way, and all along from base to tip they are covered with little glistening beads which sparkle in the sunshine. And to this the plant owes its pretty name of "dew- leaf."

Of course, as you will have guessed, these shining beads, which make the little dew-leaf look so charming, are not dew. They are produced by quantities of little glands all down each side of the leaf. These glands are red like those on the tips of the tentacles of the sundew; but if we look at them through a magnifying glass we see that in shape they are just like little mushrooms, reminding us of the sticky glands on the leaves of the butterwort. Besides these red mushroom glands the lower part of each leaf is crowded with quantities of tiny pocket glands. These are colorless, and until they have been touched by a crawling insect, or anything else good to eat, they are quite dry. But on every little raised red gland there is always a tiny bead of clear, sticky fluid, and when these are brushed away fresh drops at once ooze out to replace them.

In the dry sandy places and on the bare rocky ground where this little plant flourishes the "dew-leaf" must be a refreshing sight to crawling and flying insects; but should a hapless fly alight upon one of its glittering, snakey leaves, it will never spread its gauzy wings again.

The fly is not at once glued fast to the leaf, as it would be if it popped down on a sundew or a, butterwort, but as it crawls about the leaf it brushes the glittering beads from the heads of the mushroom-shaped glands, and they instantly stick to its wings and its legs and every part of its hairy body that comes in contact with them. Every movement, of course, makes matters worse, and the poor fly drags itself slowly and painfully along the leaf, gathering more and more sticky drops as it goes. At last it becomes so plastered and clogged with the horrid stuff that it can crawl no more, and the fly gradually sinks down to the lower part of the leaf.

By this time, as you may suppose, the fly is dead. It has been suffocated by the sticky drops which cover it and clog its breathing pores. Then having caught and killed its prey, this strange fly-catcher proceeds to dissolve and digest it at leisure. To do this it pours out upon its victim a strong acid juice from the tiny colorless glands which until they were touched by the fly, as it rolled down upon them, were perfectly dry. So you see this plant actually manufactures two different kinds of fluid--a thick, sticky fluid to catch its dinner, and an. acid juice to dissolve and digest it.

The number of insects caught by the flycatcher is sometimes quite surprising. Often every leaf will be crowded with flies and ants and tiny moths, some still struggling, some newly killed, while of others nothing but the empty skin remains. And in this condition the plant looks anything but charming, and does not deserve such a pretty name as "dew-leaf."

The peasants in certain parts of Portugal actually hang these sticky plants up in their houses to catch the troublesome flies that swarm there in great numbers in the hot summer weather, and in this way the flycatcher is turned to some use.

There are several wild plants in the fields, by the wayside, and in the hedgerows of our own country commonly called "catchflies," because they have sticky leaves and stems, and flies and all sorts of little insects are usually to be seen sticking to them; but we must not suppose they are all plant ogres. In many cases the sticky coating is there to keep ants and tiresome green-flies at a distance, and prevent them from rifling the flowers of their stores of honey and pollen, and if they will trespass, to punish them for their audacity by holding them prisoners.

Of course the insects caught in this way die. And having killed their enemies many plants are content to allow the sun to dry the dead insects, and the wind to blow them away. But in almost every case where the sticky-leaved plants live on soil too poor to furnish them with sufficient nitrogen to enable them to grow strong, and hold their own in the struggle for life that is always going on, both in the animal and the vegetable world, the plants have learned to use the captured insects as food to supply them with the nourishment they cannot obtain in any other way.

Plants, like animals, learn their lesson very gradually, and alter their ways by slow degrees to suit the circumstances in which they are placed. So among the plants that live in waste places and on boggy ground, or in cracks and crevices in rocks, we find some that struggle on, making the most of' what little strengthening stuff they can drain from the poor soil with their roots; others just beginning to discover that such things as insects are good for food and trying in various simple ways to catch those that visit them; while here and there we come across experienced plants, such as the sundew and Venus's fly-trap, provided with the latest invention in insect-traps to catch their dinner, and a perfect digestive system to enable them to enjoy it.