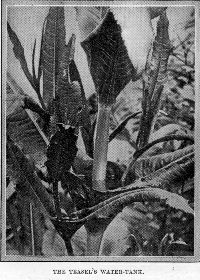

THE TEASEL'S WATER-TANK

Although, as you know, plants drink with their roots, sucking in the moisture from the soil with their delicate root-hairs, all those that catch and feed on insects are, of course, able to take in liquid through their leaf-skins as well. They have as a rule special glands through which they discharge the fluid that is so deadly to the captured insects, and through these glands, or sometimes through a different set, they suck in their insect broth.

But many plants beside these "plant ogres" are able to take in a certain amount of liquid through their leaves. They have openings in their leaf-skins (too small to be seen except under the microscope) which correspond to the glands of insect- feeding plants; but they are used only as extra mouths for drinking, and do not discharge sticky acid fluids.

But the water which the plants drink with their leaves is very rarely pure. The rain before it is sucked in by the thirsty little mouths usually gathers all sorts of dusty particles from the air, and from the stems and leaves over which it has trickled. Many plants, too, have special little pits and hollows in their leaves, which act as rain-water tanks to collect the drops that trickle down the stems.

Odds and ends of all kinds are washed or blown into these little reservoirs dust and pollen and tiny dead creatures, and sometimes little insects fall in and are drowned. These things decay in the water and so help to make a strengthening mixture, which is very good for the plant when taken in small doses through, the tiny pores in its leaf-skin. Sometimes these reservoirs are formed by every pair of opposite leaves being joined together at the base round the stem of a plant, each pair forming a regular cup, which is almost always full of water.

These little reservoirs are useful to the plant in two different ways. They form little moats over which troublesome crawling insects cannot pass, and so the flowers are protected from unwelcome visitors who would steal their honey and give them nothing in return; while the water and all the odds and ends the cup contains makes the strengthening mixture needed by the plant to help it to grow strong and vigorous.

The wild teasel has its leaves united in this way. They form quite large cups round the stem, which, even in dry weather, are almost always more or less full of water. The teasel grows on waste ground, where the soil is poor and dry, so this reserve supply of water is very useful to it, for even in the driest season it is rarely without moisture. All the rain that falls on the plant runs off the leaves and down the stem into the private watertanks; every drop is collected and stored up. So when other plants near by are withering for lack of water in the hard, dry ground in hot, sultry weather, the teasel is quite happy and does not suffer at all. But you would not care to drink the water standing in the teasel cups, for it looks and smells most unpleasant. It is nearly always a dirty brown color, and generally has a thick sediment composed of dust and the remains of dead creatures that have been drowned in it.

The teasel is a stout, sturdy plant, well able to take care of itself and provide for its own needs. It grows up straight and tall, often reaching a height of six feet or more, and with its sharp, stiff prickles it defies the attacks of all the hungry animals that come browsing near. The teasel is one of the prickliest of plants; its stems, its leaves, and even its large handsome flower-heads, are all armed with long, sharp spines. You cannot touch it without pricking yourself, and the boldest animal would shrink from having its tender mouth pierced by those sharp, needle-like spines, and so the plant is well protected against all four-footed enemies.

But bees love the teasels, and on all sunny days there is a constant humming and buzzing going on round every patch of these prickly plants, as the busy little insects flock to gather the honey from the handsome mauve colored flower-heads; and in Yorkshire, when the country folk see a crowd of people, they often say they are "as thick as bees round a 'tazzle' field."

The long-shaped flower-heads, which are made up of hundreds of tiny separate flowers all packed together as close as can be, are raised proudly aloft at the top of the tall stout flower-stem to attract the attention of the little winged pollen-carriers.

But if creeping insects, such as ants, beetles and earwigs, which are of no use to the plants, think they would like to share the feast of honey with the bees, they find they cannot reach the teasel head. Before they have travelled very far up the prickly stem their progress is barred by a pool of water; and, as there is no drawbridge over this moat, they find they can go no farther in the right direction. So the disappointed insects must needs go back the way they came, unless, indeed, as often happens, in their eagerness to discover some way of crossing the water they overbalance themselves and tumble headlong in.

Some may be lucky enough to scramble out again and finally reach the ground, sadder and wiser insects, for there are no sharp teeth or downward pointing hairs on the inside of the teasel cup to hold them prisoner, as there are in the traps of the pitcher plants ; but a great many insects are drowned, and added to the other ingredients in the cup, and so help to improve the strength and flavor of the mixture.

Of course now and again one of the struggling insects will manage to scramble on to the stem which rises from the center of the moat, and so travel a little farther on the upward path; but it soon reaches another moat, and so is in fresh difficulties, and with water above and water below the poor thing has small chance of escaping alive.

One member of the teasel family, called the "Fuller's teasel," was at one time much cultivated for the sake of the large heads, which are set in a ring of stiff hooked bristles called "bracts." The heads were set in a frame and used in the manufacture of cloth, the hooked bracts catching up and removing all the little pieces of loose wool and raising the "nap" of the cloth, as we say; and although all sorts of methods have been tried for this particular kind of work, nothing quite so good as teasel heads for "teasing cloth" has yet been found.

Fuller's teasels are now chiefly cultivated abroad, in many parts of Europe, but at one time teasel fields were not uncommon in Somersetshire and Yorkshire. The men who cut the heads wore a kind of waterproof smock to prevent their clothes being drenched with water from the teasel cups, and their hands were protected from the sharp prickles on the plants by thick leather gloves. The heads were tied up into bundles according to their size; the largest heads, which grow on the top of the stem, were called "kings," the next in size "maidens," and the smallest "buttons."

Among other plants which have special receptacles for catching and storing the raindrops that trickle over them is one found in Brazil, belonging to the pine-apple family. Its leaves are arranged in rosettes, in such a way that regular little cisterns are formed in the center, in which wee water-creatures swim about merrily.

Strange to say, in these little natural cisterns a bladderwort is often found, busily engaged in catching the tiny animals swimming about in the water in its cunning traps. As there is not very much room for the bladderwort to grow in one of these little cisterns, it sends out runners, like a strawberry plant, which arch over from one cistern to another. There the bladderwort puts forth a new set of leaves and bladders to catch the little creatures it contains. And in this way the bladderwort poaches in the private waters of several plants growing near together.